Christmas Shopping

Cognitive Overload: When Familiar Skills Suddenly Collapse

My friend was visiting the UK, driving in Cumbria. He is an experienced, sensible Aussie driver but had never driven this hire car before and never been on narrow icy roads populated with homicidal, tractor-driving locals. It was 3:30 pm and the last watery rays of the winter sun dropped below towering hedgerows. The driver starts to feel a strange pressure in his chest, a sense of panic and impending doom. He is close to shutting down, stopping the car, and getting out into the freezing gloom.

What is going on? He knows how to drive. There is no accident, no obvious single reason to falter.

Same man. Same brain. Different car, different roads, different light, different weather, different speed, different rules, different instincts. Suddenly something he had done effortlessly for decades becomes frightening. Overwhelming. Exhausting. His brain is flooded with unfamiliar inputs and his bandwidth collapses. Not because he is incapable, but because the context changed faster than his automatic systems could adapt.

That is cognitive overload in its purest form.

Brain Injury and Invisible Overload

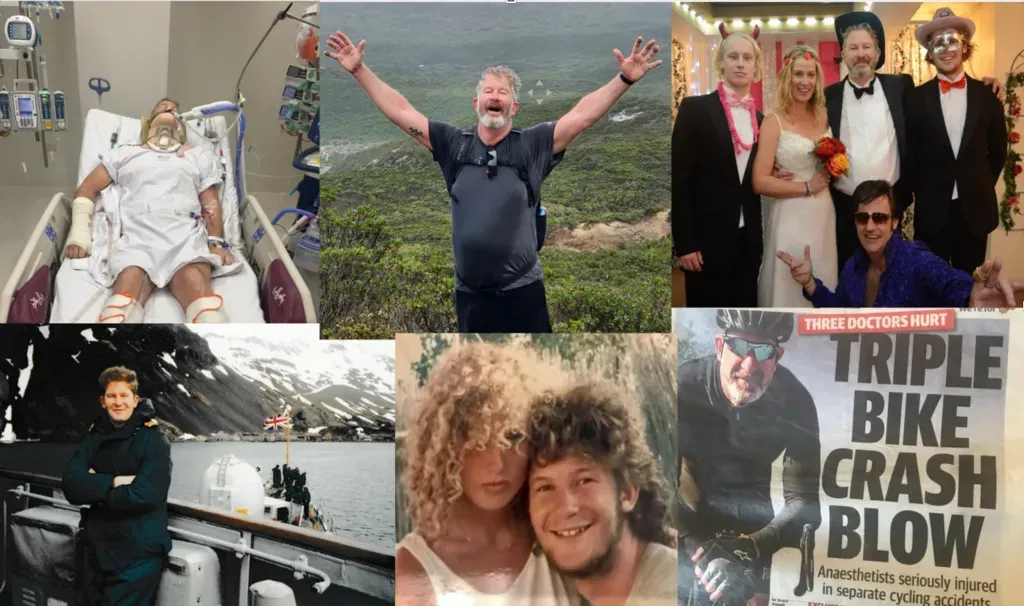

I met a man yesterday, a PhD, a consultant with a chemical engineering degree from Cambridge. He suffered a brain injury a few months ago. Now he is struggling. He looks fine, no drooling or limping; he went back to work; he runs every morning; he answers his emails; he goes to the scheduled meetings in his calendar. He even went to a charity party for survivors of brain injury. Suddenly the music was too loud, the voices too demanding, the faces too complex to understand.

He ran out. Ran home. Safe.

High Performance, Bandwidth, and Automaticity

I spent the last few days listening to jet pilots, NASA astronauts, and trauma clinicians talk about this exact phenomenon. How to manage bandwidth. How to filter noise. Elite people learning how to protect decision making under stress. How to preserve automaticity. The thing is, the PhD chap was elite, is elite, but he was overcome.

Most of us do not realise that our cognitive automaticity normally lets us ignore most faces, most voices, most expressions, most background sound, most emotional signals. We do not consciously choose this. Our brain simply filters it. That filtering is what makes life feel manageable.

Take that filter away, and the world becomes Cumbria in the dark, charity disco, space shuttle engine failure or poisonous gases, shootings, and multiple burns.

Why Brain Injury Care Lags Behind What We Already Know

This phenomenon is familiar to brain injury communities and yet support groups and health professionals still struggle to understand the experience.

The irony is that we understand how to manage cognitive overload. High performance communities train for it relentlessly. Yet we do not translate those same principles to brain injury care. We do not teach filtering. We do not teach prioritisation. We do not teach cognitive load management as a survival skill.

We should.

Excellence Is Not Optional

NASA pilots and trauma specialists must excel when they are working.

Those living with a brain injury will have to excel just to shop for Christmas.